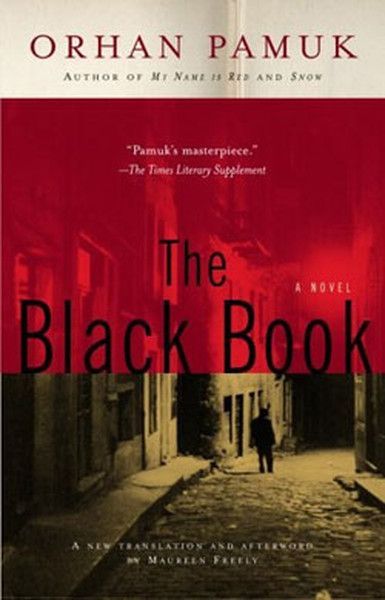

Dark Airshaft in The Black Book

Orhan Pamuk's internationally acclaimed novel has been reviewed and criticized by many; yet certain chapters of the novel received a lot less attention compared to, for instance, "When the Bosphorus Dries Up." So, I've decided to write about a chapter which has been somehow disregarded as far as I am aware: "The Dark Airshaft." In this chapter, Celal, a columnist, writes about a “bottomless pit” that was once next to the building where he spent his childhood. He says that so many stories and speculations were invented about the mysterious pit. Later, it was covered and another building was built in its place which resulted in an airshaft between the two buildings. With this narrative, this chapter explores the spatial changes in our century which is crucial in marking the shift from modernism to postmodernism and observes our reaction to these changes as a society.

“The Dark Airshaft” is very symbolic of the change from the abstract, universal and mysterious to the concrete in postmodernism. Celal remembers that the bottomless pit “made [him] shiver at night” and that he used to imagine it to be “of mythic proportions, thick with bats, rats, scorpions, and poisonous snakes” (Pamuk 483). He further describes it as a “black and timeless void” (Pamuk 484). Celal's description also relies only on the stories the residents used to invent; he writes: “[The pit] haunted us all, casting shadows over our lives like a secret sin” (Pamuk 382). Through this, he returns to the past when there used to be such places that were unknown, infinite, which one could make up stories about. On the contrary, now, as Fredrick Jameson's places of postmodernity, the places in Kara Kitap involve “a relentless saturation of any remaining voids and empty places.” The pit has been pushed completely to the surface; there is nothing hidden that asks for speculation and imagination anymore for most people. However, Celal writes that the “nightmare was not yet ended; the terror had only just begun” (Pamuk 382).

So, the problem of representation that the pit presented to the residents gets annulled, but another problem emerges. Celal describes this new gap as filthy, disgusting, full of bad odors, and the residents of the building think of this gap as “the crucible of evil” (Pamuk 489). The residents are intimidated by this air-shaft as “if it were a fear they were desperate to escape and forget forevermore” (Pamuk 385). With the vanishing of the idea of the unknown and mysterious distance, the marginalized is now uncannily close in the city which upsets people more than ever.

Celal turns this marginal space of the air-shaft into a strategic positioning as he recounts people like children, the servant girl, a deaf-mute, an old woman who are outcasted, spend time daydreaming as they stare into the air-shaft, seeing the shadows of people and lights from other windows (Pamuk 387). He writes about the airshaft to “ envelop and develop this marginality . . . a strategic positioning that disorders, disrupts, and transgresses the center-periphery relationship itself” as Soja tells about in his book Thirdspace (84). Thus, the air-shaft also becomes a space of motility and potential that is open to the play of human imagination, a space of social struggle that nests certain people, a space that is disregarded by the dominant order, nevertheless able to resist it like the Thirdspaces of Soja. While writing about these people, Celal writes “God be thanked, there is always someone willing to rummage through the forbidden pages” (Pamuk 489). He refers not only to the people who challenge the dominating discourse around the air-shaft, but to himself who has access to the othered parts of the city and who can transform them through imagination.

So, the chapter "The Dark Airshaft" delicately explores our spatial imagination in relation to the shift from modernism to postmodernism. I hope this short post encourages readers to pay more attention to the novel's widely disregarded content, particularly to dynamics of its narrative space, as opposed to its often and justly praised structure.