How to deal with your unexciting life: Reading Stoner by John Williams

This novel is thought-provoking for a modern audience because we confront the threat of nihilism by trying so hard to be somebody, to differentiate ourselves from people in the past, and from the repetitive nature of the work we do.

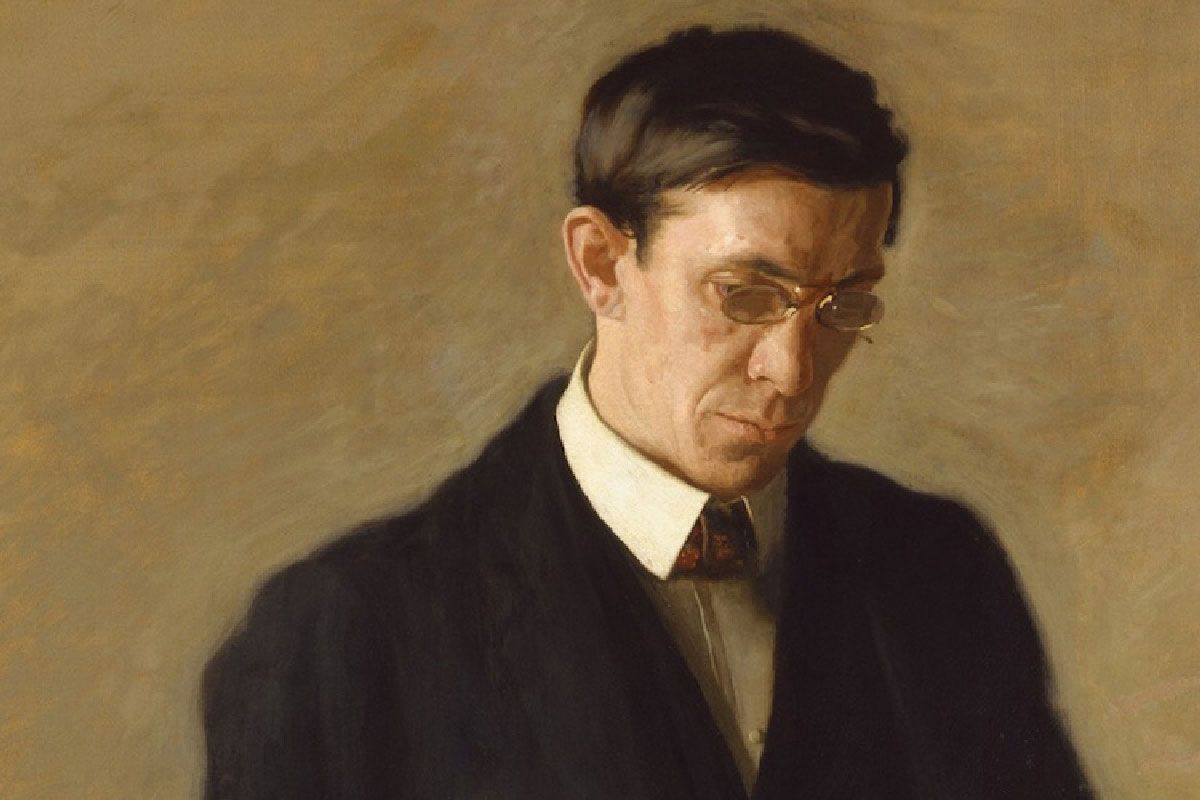

As we are being bombarded by social media with artificial images of luxury and extravagance, John Williams' novel Stoner feels like a breath of fresh air. The novel is about a man called William Stoner who is born to a poor farming family. Initially enrolled in the agriculture program at the university, he later decides to pursue English with the encouragement of a professor named Saloene and ends up becoming an English professor.

More generally, this novel is about the cloistered existence of people who are devoted to the unglorified work they do. The first is William Stoner's father who dies while working on the field. Shortly after, Stoner loses his mother, probably from the grief of loss:

Now they were in the earth to which they had given their lives; and slowly, year by year, the earth would take them. Slowly the damp and rot would infest the pine boxes which held their bodies...and finally it would consume the last vestiges of their substances. And they would become a meaningless part of that stubborn earth to which they had long ago given themselves.

This impersonal tone persists until the end of the novel. The cyclical nature of existence described here can be understood as a general description of the life and death of the people who stoically devote themselves to their work. Like his father, Stoner's mentor Prof. Saloene dies sitting on his office chair on a Friday evening:

He had remained the whole weekend at the desk staring endlessly before him. The coroner announced heart failure as the cause of death, but William Stoner always felt that in a moment of anger and despair Sloane had willed his heart to cease, as if in a last mute gesture of love and contempt for a world that had betrayed him so profoundly that he could not endure in it.

As students leave for World War I and never come back, Sloane is overcome by a sense of loss. He dies sitting at his desk contemplating. William Stoner's idea that Sloane willed himself to die is a reflection of the indifference of people like Sloane to their individual faiths. They perceive their lives and deaths as neither authentic nor personal. They are therefore capable of thinking of their death as the death of an ambiguous someone.

The third-person narrator penetrates Stoner's thoughts and feelings but conveys them almost in the manner of a biology textbook. His life does not move toward a personal death. Instead, the novel draws attention to the common life experiences of dedicated academics. Stoner, too, witnesses students leave the university to fight in World War II and his health, too, rapidly declines after years of searching for the truth, always imagining that he will find it in the next book while knowing very well that he will not.

When Stoner learns about the severity of his health condition, he feels "nothing at all; it was as if what the doctor told him were a minor annoyance, an obstacle he would have to somehow work around." With a curious indifference to his personal situation, he decides to complete some important tasks and make arrangements for some of his responsibilities. Showing no sign of internal distress, the goes through these tasks before his surgery.

Yet this kind of indifference is presented as neither a sign of depression nor giving up on one's life. What separates these people from others is that they are so truly devoted to their work that they perceive it as beyond their individual existence and feel no reason to prove to themselves the authenticity of their work and individuality. Devoting their lives to a certain occupation, they become a part of it and see themselves as such from an impersonal third-person point of view.

This novel is thought-provoking for a modern audience because we confront the threat of nihilism by trying so hard to be somebody, to differentiate ourselves from people in the past, and from the repetitive nature of the work we do. Essentially, this novel asks if there is also dignity and possibly happiness in resigning oneself to the unoriginality of the work one does and to the cycle of existence.