Advice on writing from Annie Dillard

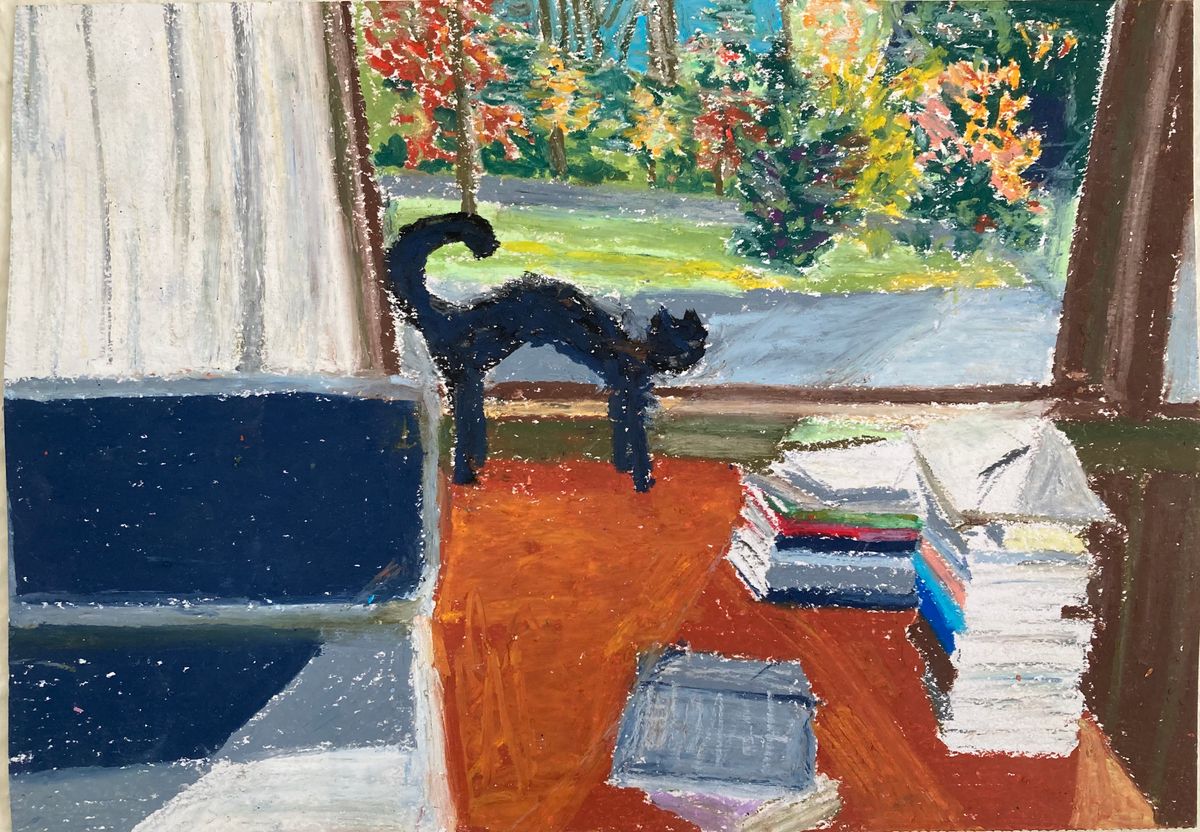

The Writing Life by Annie Dillard would resonate with anyone who has ever taken up some kind of creative work. A lifetime of wisdom about life and writing is condensed into a slim book of 111 pages. Loosely connected descriptions, anecdotes, and analogies somewhat form a full account of creative expression. In this post, I will discuss, at the risk of oversimplification, some of the major takeaways from the book, on reasons to write, how to write and what to write.

Why write?

For Dillard, writing is "life at its most free, if you are fortunate enough to be able to try it, because you select your materials, invent your task, and pace yourself" (The Writing Life). But there is a cost to this freedom. She adds: ". . .your work is so meaningless, so fully for yourself alone, and so worthless to the world, that no one except you cares whether you do it well, or ever" (The Writing Life).

Dillard touches on the essence of creative work in this book when she says there is no demand for it. She explains that if a "shoe salesman fails to appear one morning, someone will notice and miss him;" yet no one, she believes, will feel the same way about a manuscript. Before words are put on paper, writing is known to no one but one person, the self.

Since Descartes' claim "I think, therefore I am," the concept of the self has been largely contested by philosophers. And with the rise of artificial intelligence, the idea that thinking and reasoning are above everything else has proved inaccurate. Now we know that thinking, just like any other bodily function, can be replicated by science. And from a sociological point of view, the self is nothing but a reflection of society's common beliefs and discourses.

Returning to what Dillard said, we can perhaps anchor the concept of the self in writing or other creative pursuits. Putting something creative out there becomes a way of objectifying the self, turning it into something tangible.

One reason to continue doing creative work is that no one else other than you can do it. There is indeed no tangible demand to do it, but there's almost a larger, existential reason to continue.

How to write?

In the later parts of the book, Dillard complicates the idea that writing is a reflection of the self.

She mentions the poet Saint-Pol Roux, "who used to hand the inscription 'The poet is working' from his door while he slept" (The Writing Life). It is strange to think that many good ideas emerge during the unconscious state of sleep. We still use the word muse, invented by the Greeks, to refer to the mysterious source of inspiration. It remains ambiguous whether inspiration comes from an external source or a place within the self.

So not being able to come up with a sentence for a long time is a part of the process and there is not much sense in worrying about the pace of writing.

Citing a West African proverb, Dillard acknowledges that inspiration does depend on external factors to a certain extent: "The beginning of wisdom is to get you a roof" (The Writing Life).

But when the inspiration does come, Dillard's advice is to use it all. She writes:

"The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. . . Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes" (The Writing Life).

This is probably one thing that resonated the most with me. If I think about writing something but decide to do it later, something gets "lost." When I sit down and reconsider, what remains is "ashes," the remnants of something meaningful.

It is best to write at that very instant that inspiration comes. The Writing Life seems to be a collection of such instances. Dillard seems to have written these occasionally disconnected pieces of wisdom as they appeared to her.

Dillard expresses this urgency with an anecdote:

"After Michelangelo died, someone found in his studio a piece of paper on which he had written a note to his apprentice, in the handwriting of his old age: "Draw, Antonio, draw, Antonio, draw and do not waste time" (The Writing Life).

What to write?

"If [people] don't like to read they will not. People who read are not too lazy to flip on the television; they prefer books. I cannot imagine a sorrier pursuit than struggling for years to write a book that attempts to appeal to people who do not read in the first place" (The Writing Life).

Coming to think of it, movies and books are entirely different. We often expect a movie adaptation of a book to be similar to the book itself, but it simply cannot be. Movies always come first; reading books require extra effort and commitment. They are not interchangeable. No one would consider watching movies instead of reading or vice versa; they are different activities.

The two being almost entirely different experiences, Dillard is arguably right in saying that writing for an audience that doesn't read is a vain pursuit.

When thinking about what to write, it might be best to write something that could appeal to an audience that reads because the opposite would mean distorting one's writing to make it interchangeable with something else.